Welcome to the first of a two-part series, ‘Creations from Twenty-Twenty’, which focuses on two mini-projects I worked on during last year’s lockdown. Hope you enjoy it!

* * * * *

This is a story about languages. But not quite.

Having moved to a foreign country at a young age, I never properly learned my mother tongue. While I grew up speaking Cantonese at home and occasionally practiced the Mandarin I had picked up from watching television shows, I never learned to read or write Chinese. And outside of one childhood summer when my mom attempted to teach me (lessons which I promptly forgot once school started), I never made another proper attempt.

Fast forward to last year. I purchased a textbook filled with Chinese characters1, and sat down with a notebook to learn and practice writing the characters one by one. Besides simply memorizing new characters each day, I also read about Chinese radicals and character classifications – for example, compound ideographs (會意) versus phono-semantic compounds (形聲).2 This helped me better understand how to recognize characters as well as learn the correct order of strokes for writing each one.

Soon, the pages of graph paper in my notebook began to fill up with repeated copying of characters from the textbook. However, this progress also came with two problems.

The first was on testing myself. I was slowly increasing my mental repository of Chinese characters and their meanings, but how do I check that I’ve retained this knowledge over time? What’s to say I wouldn’t forget the first twenty characters when I move onto practicing the next twenty? I also had to consider the different angles to developing recognition. Could I successfully write the characters based on pinyin or English translations, and vice versa?3

The second problem was that, like all learning materials, there were limitations to the textbook I was using. In this case, while many of the characters included could be useful in everyday conversation, some seemed less relevant (Do I really need to be copying down 巫, for “shaman”?). The textbook also did not cover components such as prepositions (What is the Chinese character for “of”?), which I needed to learn in order to move into reading and writing Chinese in full sentences.

So how could I solve these two problems?

* * * * *

Enter: Python, one language to help me learn another language.

When it came to assessments, I had initially tried self-administering “tests” by writing down all the characters I knew on scrap paper and then comparing them to what I had repetitiously practiced in my notebook. But this quickly became more of a memory exercise than actually evaluating my familiarity with Chinese. It also felt wasteful to add to a stack of paper each time I made up a new quiz.

So, I decided to write a program that could test my knowledge through multiple methods. The program had a simple objective: create a randomized list of words by pinyin and/or English translations, which I would then use to practice recalling Chinese characters by writing them on my tablet.4

I named the program, scramble_chinese. Sometimes it reminds me of breakfast.

But before it could output a list of words, scramble_chinese had to “know” the dataset of Chinese characters that I had already studied. To accomplish this, I typed the contents of my physical notebook into a Google Sheet, which my program could then access via Google APIs.5

This was the most manual part for my testing process, and continues to be even today as I learn new characters. However, I ended up finding the Google Sheet quite useful for keeping track of what I had studied, especially as list of characters grew. After all, it is quicker to search a virtual document than to sift through sheets of paper in a notebook.

Once I connected scramble_chinese to the Google Sheet, I added user options to make the program more customizable. One setting dictated how many characters I wanted to be tested on (ten characters for a “pop quiz” and fifty for an “exam”). Another switched the test output between English translation, pinyin, and Chinese characters for different types of assessments.

Now that I had a more automated approach for testing myself, I moved on to solving the second question of expanding my Chinese beyond the textbook.

* * * * *

When I first started learning to write Chinese, I read somewhere that a person needs to know roughly three thousand characters to be able to read a Chinese newspaper.6 Since my textbook contains only several hundred, I thought perhaps news articles could be the next source for learning new characters.

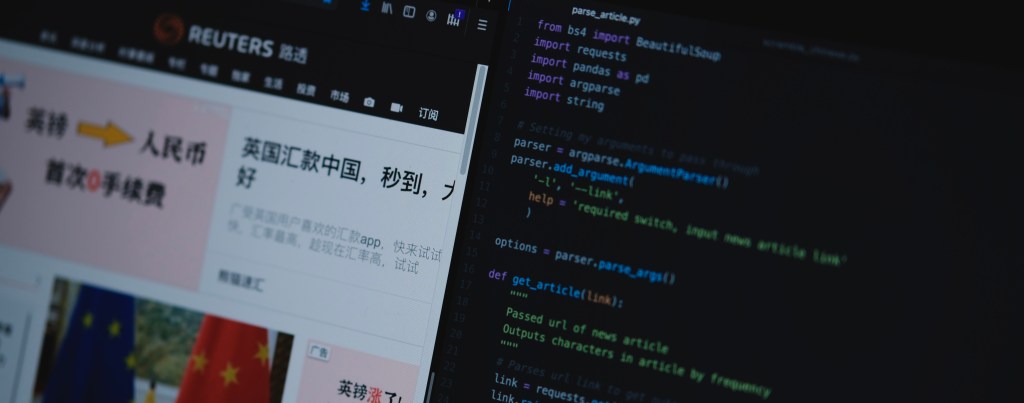

I started by writing a program to read any given Chinese article from a website – let’s say, the Chinese version of Reuters. The program then identifies and displays the most repeated characters used in the article.

I named this program, parse_article, for lack-of-creativity reasons.

The first part of coding parse_article was figuring out the html structure of different news posts to make sure the program scanned only the actual article rather than the side headlines and advertisements that may show up on the webpage. And because this was focused on Chinese, the program splits up the article’s text into a long list of individual characters.7

Next, I focused on removing alphanumerics from the long list so that the program displayed only Chinese characters. While this was simple for letters and numbers, I have to admit that in the end I included a line of code specifically removing a hardcoded list of different variations of commas, quotation marks, and periods.

Finally, I limited parse_article’s output to the top fifty most common characters in an article, figuring this would capture the ones I needed to learn to build up basic reading comprehension and writing abilities.

When the program was completed, I held my breath and passed in news articles to see what the results would look like. As an example, a recent BBC post on Mars exploration (in Chinese) yielded the following top-ten results of Chinese characters and its frequency in the article:

的 128 (Of)

们 59 (Suffix, plural marker)

生 58 (To be born; birth)

在 54 (At)

物 46 (Thing; object)

星 46 (Star)

一 35 (One)

有 34 (To have; to be)

我 33 (I; me; my)

可 30 (Can; able to)

Success! All of these characters are quite common in everyday speech. Some may not be as useful by itself (how often would I read about stars, 星?) but could be more relevant as parts of words (say, if I want to read about celebrities, 明星…for the gossip of course).8

I was happy to have completed the programs and could continue with my Chinese learnings. For those who are interested, here are the Github links for scramble_chinese and parse_article. A quick note: I am as much an amateur in coding/Python as I am in Chinese, so any suggestions (on either language) would be much appreciated!

* * * * *

After the few days spent on writing these two short scripts, the natural question I had to ask myself was, “Does this help me learn Chinese more easily?”

The short answer: Yes. But not quite.

I joked with friends and colleagues that I probably learned more Python than Chinese from this mini-project. And in the months since, my self-planned Chinese lessons have faltered and slowed after progressing to several hundred characters. I put this down to negligence and distractions, both of which cannot be solved by my code.

Still, from time to time, I do pick up my notebook and practice writing new characters, most of which I pick up from parse_article and then test myself via scramble_chinese. I also think about how I could improve these programs. For instance, it could help to add some basic natural language processing (NLP) techniques to split a news article’s text and capture common multi-character phrases or words.9

Who knows? Perhaps by writing more Python, I might just end up learning some Chinese.

Footnotes:

- I had gotten the Chineasy Everyday book, which is quite fun in that it is very visual by turning every character into a picture. However, I feel this gives the unintended impression that all characters are pictographs (which they are not; see below). I should also note this textbook does not follow a lesson-by-lesson structure and instead functions more like a reference book.

- There are several Chinese character classifications, with phono-semantic compounds being the most common. These characters typically consists of two or more building blocks, one to indicate the sound and another to indicate the meaning.

- Here, I am referring to Hanyu pinyin, which is the romanticization system for Mandarin.

- I should note that I’m really fortunate to have a tablet and this is of course not needed! That said, I am also not sure why I didn’t just start with makeshift quizzes on my tablet in the first place…

- How lucky we are to be learning programming in an age of limitless resources! The Google Sheets API documentation was super easy to follow and use.

- Of course, reading a newspaper also requires contextual knowledge of a language and the culture involved.

- This means that, technically, parse_article could be used for Korean or Japanese new articles too!

- In Chinese, “celebrity” can be written as “明星”, which literally translates into “bright star”.

- In natural language processing, this technique is known as tokenization. I also found a library for segmenting Chinese, called jieba (which is pinyin for 结巴, meaning “to stutter”, haha).