Introduction

There is no way to write an inoffensive thought piece on the protests taking place in Hong Kong. It will enrage at least some people and resonate with a few others. My hope is that it pleases no one and angers just about everyone.

This is an edited collection of notes from my visit to Hong Kong and Shanghai in August. It was a trip I had planned for seeing friends and family, and for rekindling memories with my childhood cities.

Please read with care!

* * * * *

Part 1: Helmets in Hong Kong

What surprised me was the quiet.

I arrived at Hong Kong International just a day after protests at the airport had ended. Posters advocating for “Freedom!” and “Democracy!” had already been removed. The scene was instead spotless and noticeably quiet. Had I not known that airport officials had obtained an injunction to clear out protesters, I wouldn’t have guessed that demonstrations had been taking place here for the past 4 days.

After several months of reading about escalating tensions in the city, this was not the scene I was expecting.

It was a Friday night when I caught my first glimpse of the protests. My friend and I were walking past Statue Square in Central when we came upon a small group of people dressed in black t-shirts and face masks. They were blaring the US national anthem from a boombox and one guy was waving a large US flag high above his head. His face was covered with a bandana and he led the slow-moving march.

My friend and I remarked that this was the ridiculousness of the protests that the media portrayed – it was the ridiculousness that the Chinese media would pounce on. Calling for the US was a distraction from the actual civil issues at hand and did not offer any realistic solutions for the people of Hong Kong.

At the tail end of the march were protesters collecting discarded plastic bottles and holding signs reminding their peers to clean up after themselves. This resonated more with me. We should all be marching for cleaning up the environment.

It was exciting to be so close to the protests. I thought this would be a preview to seeing more violent clashes over the weekend. After all, the past few weeks’ worth of news articles and online videos had been painting a scene of escalating tensions and outbreaks of fights across the city.

Sunday came and people with umbrellas filled the streets weaving in and out of Admiralty to Causeway Bay and other areas that I only recognized by MTR station names. According to organizers, 1.7 million Hong Kongers showed up on this day, starting at Victoria Park where a headcount was being taken. Later that night, local news channels reported that police forces had estimated the crowd size at roughly 130,000.

My friend and I went out to survey the scene in the early evening. We walked near Pacific Place and stopped at a footbridge overlooking Queensway. The road beneath was covered with umbrellas moving under the light rain. All along the glass walls of the bridge, people took out their devices to take photos and videos of the march. Many of them were protesters coming from the demonstration. There were entire families dressed in black with strollers and toddlers, getting ready to head home as night fell.

One particular moment stands out in my memories: On the footbridge was a girl dressed in a black t-shirt, black cargo trousers, and dark colored boots. She had on a heavy-duty helmet, goggles, and gas mask. On the back of her helmet, right above her ponytail, was the word “STUDENT”. She stood next to her friend, who eventually threw an arm over her shoulders as they walked into the mall.

It was a striking image because the helmet seemed to be nearly as wide as the shoulder width of the girl’s slender frame. Here was someone who is just a kid, outfitted with battle gear. There’s a romanticism to fighting for dreams as you’re just learning to grow up, as if keeping a promise you made in your childhood. Yet for all its determination, there also seemed be a sense of wanderlust, a feeling of “let’s see where the wind blows” in fighting for ideals. Maybe this is why Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five is also called The Children’s Crusade.1

That Sunday, the protests ended peacefully. But as the sea of umbrellas moved through Hong Kong Island, there were still no signs for where all this was headed.

* * * * *

Part 2: Conversations in Shanghai

I took an early Monday morning flight to Shanghai.

On the first day, I went to see family and old relatives. They jokingly asked was if I had taken part in those Hong Kong protests with those Hong Kong youths. Their impression was that the city was in shambles, all because of a younger generation who do not know any better.

Kids fighting a children’s crusade.

I responded that it wasn’t just misguided students who were leading the marches, that there were also older folks and people from all walks of life. I’m not sure if my relatives thought any more of it. Perhaps they were referring to the violent antics that generally did not involve the elderly or mothers with strollers.

My usual news consumption comes from Financial Times and the like, so it was easy to brand their perceptions as due from misinformation and lack of details – this is what I read about every day. But seeing their subjectivity (generally against the Hong Kong protests) made me question the biases I myself am subjected to.

A few nights later I was at a dinner with my parents and a few family friends. There was a husband and wife, both slightly older than me and working as high school teachers. In a mix of broken Mandarin and English, we shared our understandings and views of the protests. Questions popped up alongside plates of Shanghainese dishes served to our table.

“What was Hong Kong like while you were there?”

“Are the protests something you hear about every day in Shanghai?”

“Did you get a sense of what it is that the protesters are really fighting for?”

“How do you think the Chinese government is planning to respond?”

The husband and wife spoke out against the violent clashes between the protesters and police, and cited media stories on how the US government is paying local Hong Kongers to join the protest. But these thoughts were not signs of brain-washing or suppression, as I often hear described in Western dialogues. Instead, the tone is oddly similar to the news that I read, about how the Chinese government is sending buses of mainlanders into Hong Kong to hold pro-Beijing rallies.

To both sides I say, “Well, you’re probably not wrong.” I wouldn’t doubt it if some level of funding for the HK protest organizers came from US government agencies. Tim Wiener’s Legacy of Ashes2 has taught me to know better. And I wouldn’t doubt it if Chinese authorities did fashion a plan for counter-protest events.

By the end of the meal, the conversation had turned to life in Shanghai. We talked about how everyone uses VPN to binge-watch the latest Netflix shows. I asked if people are afraid of getting caught, but the husband shook his head. It is just how things are.

VPN to watch Netflix and secret government payments to advance national interests. It is just how things are.

* * * * *

Part 3: Taiping Rebellion and Rear View Mirrors

My favorite page on Wikipedia is on the Taiping Rebellion. This is not because the historical conflict has anything in common with current events (and I certainly hope no one is claiming to be Jesus’ brother), but because there’s a section stating “The terms used for the conflict and its participants often reflect the viewpoint of the writer.”3 We really ought to include this footnote in more publications.

Oftentimes I read about Hong Kong’s situation as being a battleground between democracy and authoritarianism. It’s lunatic how conveniently we can organize the chaos of conflicts into neat drawers and shelves, as if state actors are simply acting out the latest Game of Thrones plot lines. We get so hung up on dictating the good guys and the bad guys that we neglect the complexities of the narrative itself. But as I learned from Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes, no one really knows where the story is headed.4

Note to self: Language can just as easily be used to oversimplify ideas as to illustrate them in excessive detail. A helmet can be described as part of a battledress or as a means of safety precaution. As mentioned earlier, please read with care.

Another footnote we should use more often, as stolen from rear view mirrors: “Objects may be closer than they appear.”

Anything can be belittled or blown up by the perspective of the author. That’s how we get to crowd estimates being either 1.7 million or 130,000.5 It might seem impossible to figure out what the real number should be. The good news, though, is we have more resources than ever before to investigate. Not only are data and analytics right at our fingertips these days, technology has also allowed us to have more discussions with other people. It’s a blessing to be able to learn from those who think, see, and experience life differently. I do wish everyone would share just a few more conversations.

So before I forget: The terms used for this conflict and its participants reflect the viewpoint of the writer. Also, objects may be closer than they appear.

Sources:

-

- Vonnegut, Kurt. Slaughterhouse-five. New York: Dial Press, 2005. Print.

- Weiner, Tim. Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA. , 2007. Print.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taiping_Rebellion#Names

- https://www.gocomics.com/calvinandhobbes/1991/02/18

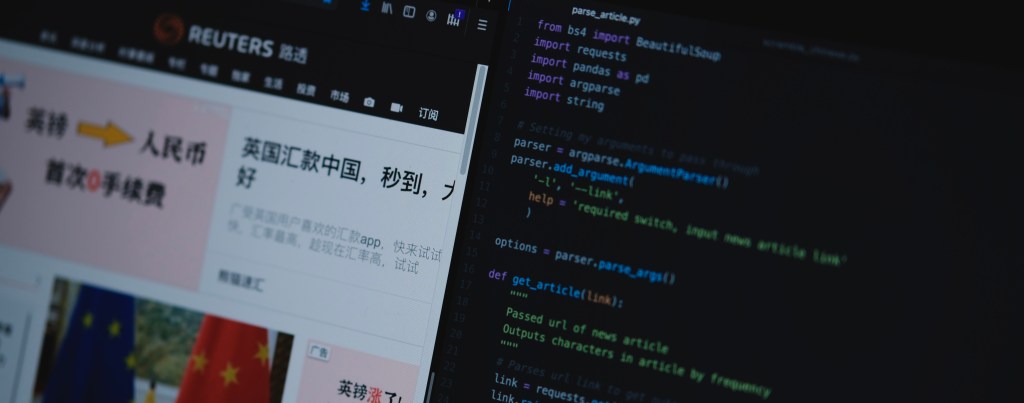

- https://graphics.reuters.com/HONGKONG-EXTRADITION-CROWDSIZE/0100B05W0BE/index.html